The Story of Joule Ready

I worked on Joule Ready for my last 2.5 years at ChefSteps. This is the story of how we defined the business and user problems for the product and how we arrived at the solution of shelf-stable sauces through multiple pivots and experiments.

What is Joule Ready?

ChefSteps started as a cooking content company, producing free content to eventually monetize through classes. At the two-year mark, we decided to build hardware—the Joule sous vide circulator. After launching Joule, we realized we had more gaps to fill for cooks, so we wanted to create a consumable product that would connect with our hardware, software, and content. It was our idea of a "full-stack" cooking company.

The way Joule Ready worked: you'd get a protein and drop it in a sous vide bag with sauce. You'd scan the bag, which would give you directions to make the food—the proper time and temperature along with Visual Doneness™. Choose the doneness, push a button, and it alerts you when it's done.

Defining the Problem

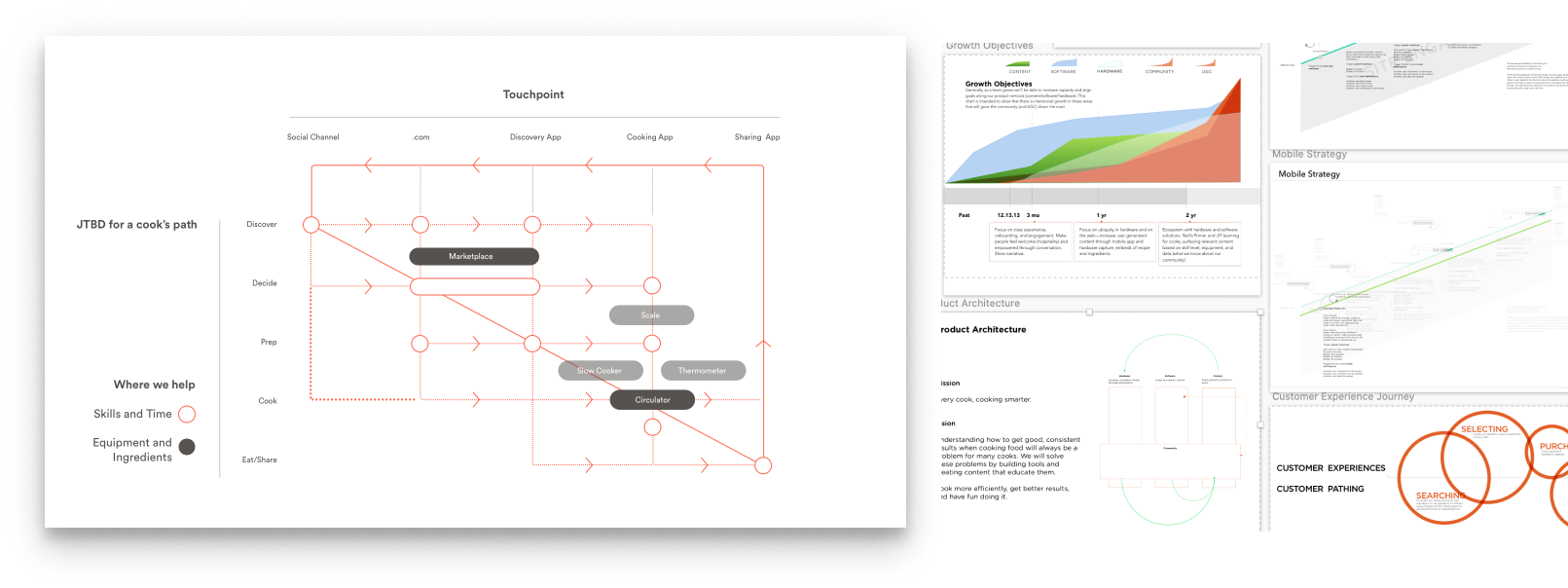

One of the early projects was trying to map out all the touchpoints for our users. What it came down to was always the gaps of skills, time, equipment, and ingredients. Time is always the hardest part—trying to convince people to value their time cooking had the most competition.

We moved from purely educational to educational plus inspirational. Our equipment was a circulator, and the final leg of the stool was ingredients to cook with. This also solved the recurring revenue model—ingredients were a way to get recurring revenue. We just had to figure out how to make the margins work.

Exploring Solutions

During the next few months we started experimenting. We iterated, tested, learned, and made changes from both the UX side and the business side to learn what was going to work.

Meat Sales

We started with the basics: protein. We offered meat for sale to Joule customers and invited them to our space in Pike Place Market. We sold a good amount of meat, but more importantly, found a great way to increase margins: sous vide upgrades.

We had solved two business problems: recurring revenue in a hardware-based model and increased margin on commodity products. This also solved user problems: time and ingredient scarcity.

Butcher Partners

We then tried to achieve growth through distribution. Shipping meat is expensive and hard, so we looked to partner with butchers across Seattle. We ended up partnering with B&E Meats and Double D Meats to create sous vide-ready packs with specific job-to-be-done packages like "Weeknight Dinners" and "Party Packs."

Butchers were one way to hit that distribution mark, but it was slow-going. My product partner got hung up on more than once—"We don't do that sh*t," they said.

Pre-cooked Meats

We experimented with ready-made meats delivered UberEats-style for dinner that evening. Turns out, not really a factor in dinnertime at all. We quickly abandoned this and went back to square one.

Joule Ready Sauces

So we started making sauces in a bag. This solved a lot of problems from the product side:

- No perishables

- Shelf-stable

- Cheap to make

- Great margin

- Easy to ship

Distribution and marketing were the biggest lift. We spun up a kitchen, bought commercial equipment, and developed awesome packaging and branding. We had distribution through our massive mailing list and were able to gain traction on sales very quickly.

The Big Job and the Little Job

We had to keep people buying the products and actually using them so they wouldn't just stay stuck in the pantry. The "Ah-ha!" moment was when they actually ate the stuff, because our sauces were great. So we thought of different ways to get people to cook and use the sauce—recipes for naan to sell Tikka Masala, "Sauce 4-ways" with different recipes. It was all good stuff; we just ran out of time.

Outcomes

Pirate metrics were good. Email was a great channel—much more lucrative than social. YouTube and Instagram conversions were scarce. One of the best things we did was a naan video that drove sauce consumption.

People loved the product and were sad when it went away after the Breville acquisition.

What I Really Did

This was a formative time in my career. I essentially ran the product team:

- Ran standups and worked cross-functionally with marketing, content, kitchen, logistics, design, and engineering

- Developed content strategy and metrics of success

- Filled gaps—online store design, front-end development in Shopify

- Packed our first batch of sauces and drove them to the post office

- Led the beta program with extensive testing including "Liking" scores and NPS for each sauce

Reflection

Joule Ready taught me that finding product-market fit is rarely linear. Each "failed" experiment taught us something essential about our users and business. The sous vide upgrades insight from meat sales directly informed the sauce concept. The butcher partnerships taught us about distribution challenges. The pre-cooked meals taught us what our customers didn't want.

The product was eventually discontinued after Breville acquired ChefSteps, but I still think there's a market for ready-made sauces for sous vide cooking. The model worked—we just ran out of runway.